Inmigración: A Human-Monarch Story

A monarch wing. Tiny scales on butterfly wings absorb heat, helping warm the insects. Credit: Sierra Hastings

“My home smelled like honeybees, and honey.” Alhondra Lopez, Utah student and Sageland Collaborative volunteer, pauses as she recalls her childhood in Guanajuato, Mexico, in a family of beekeepers.

With her father, a beekeeper with a great love of nature, Lopez remembers wandering around lakes, rivers, and hills and finding plants like the bulrush to take home. “I’d often explode the bulrushes, sending millions of ‘feathers’ flying around the house and making my mother mad,” she smiles. “But I always describe my house feeling like that—like a song from nature.”

Lopez’s parents even gave some of her siblings names that come from the more-than-human world. Alhondra comes from alaudidae, the word for the lark family, while her older sisters, Vanessa and Cynthia, have “butterfly’s names.”

An Early Encounter

Lopez recalls a “powerful experience for embracing nature,” brought through a meeting with migrating butterflies. When she was eight years old, Lopez and her family visited the Sanctuary of Monarchs in Michoacán, Mexico for the first time.

“I remember the Indigenous cultural presentation at the base of the mountain, and my first taste of a blue and green tortilla—so delicious!”

Lopez and her family were silent, taking care to respect the place as they started the hike. “It got rough for me to walk so much, as I wasn’t used to hiking in mountains. It was cold and we were in the wildlands.”

“But then, I started hearing a fluttering sound, and what I saw . . . it was like a miracle embracing the trees. Monarchs were everywhere. I remember the sunlight catching in their tiny wings, reflecting so much red. The sound of them flying was energy to my heart.”

A Long Journey

With their striking orange and black pattern, monarchs are one of the most recognized and beloved species of butterflies. And beyond their looks, they’re impressive athletes. Some travel up to 2,000 miles to find a warm place to stay for the winter. Once they arrive, monarchs huddle on trees for warmth, occasionally even breaking a tree branch with their collective weight.

While other butterflies migrate, monarchs are the only species known to make a two-way migration, the way birds do. But it gets even more interesting: these migratory paths happen over multiple generations. And just how this tiny insect—about the weight of a pumpkin seed—accomplishes such a navigation feat, and over timescales beyond its own lifespan, is still a mystery.

Interspecies Migrations

“Migration is hard,” says Lopez, who made a similar journey to the monarchs she watched in such awe as a child. She came to the U.S. to study at 15 years old.

“In my case, I had to learn a new culture, new ideologies, and a new language, which was a nightmare.” Lopez says that finding a sense of belonging has been particularly difficult. She faced silent bullying by classmates in high school and continues to deal with mistreatment for speaking English as a Second Language. Despite these obstacles, Lopez says, she feels proud that she graduated with her Associate's Degree in Film Production Technician with honors. In summer 2024, she will graduate from Westminster University with her double Bachelor’s in Fine Arts and Environmental Studies with honors.

“Resilience,” she says, “has been a close part of my identity. I believe that in order to keep moving forward, it is necessary to change, like monarchs. They migrate when it is cold to find new, warm chances. It takes some generations for them to get there, and they don’t know if the promise will hold out. But the hope is there.”

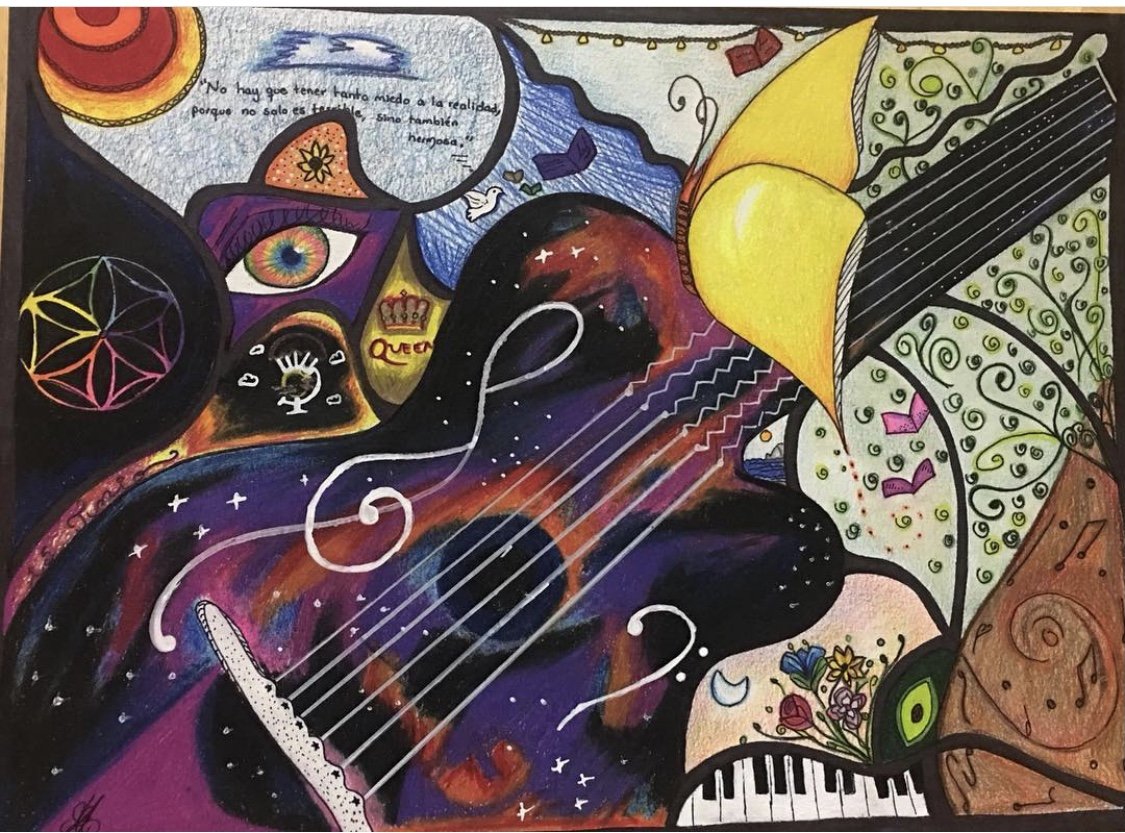

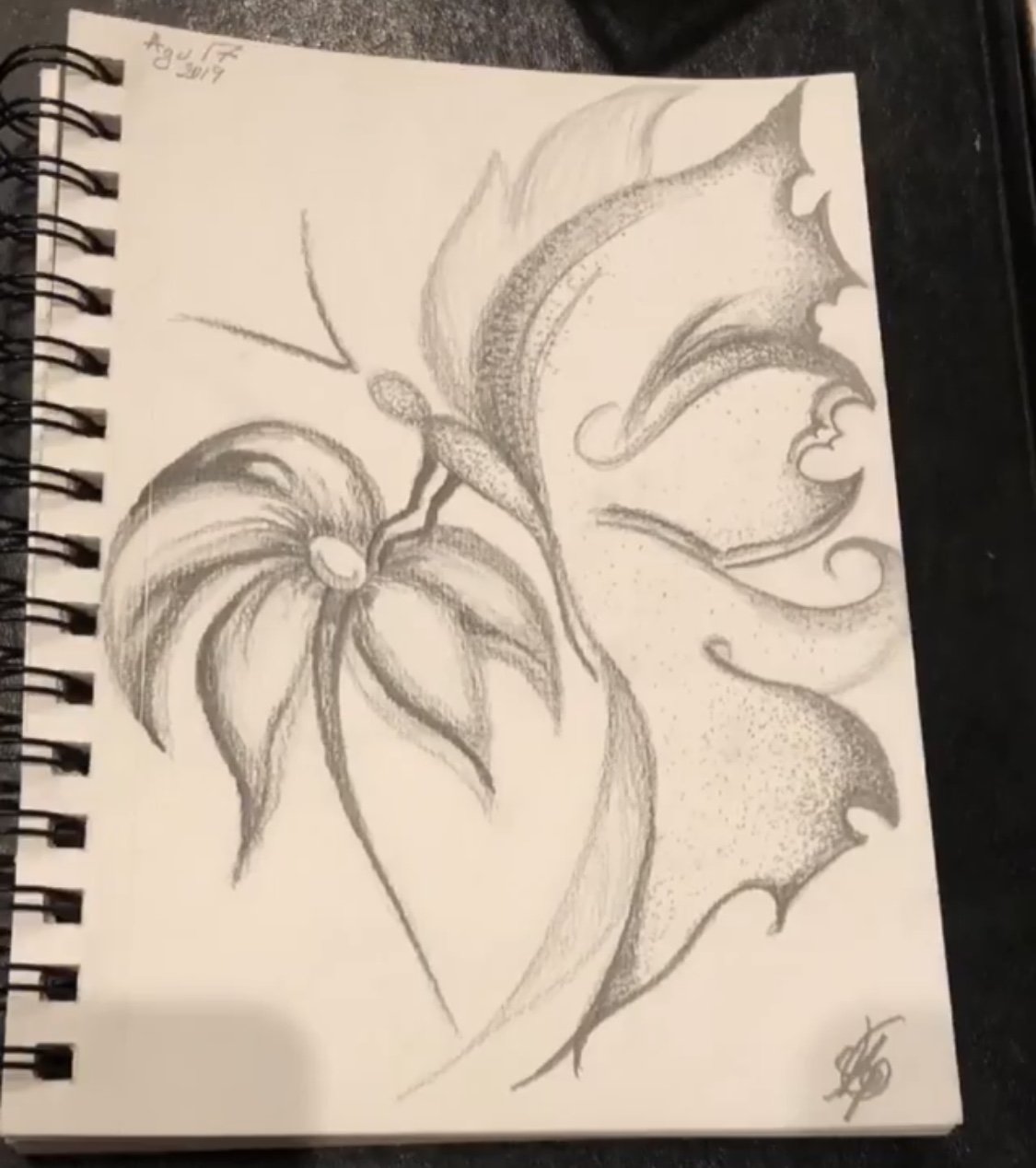

Lopez is a sculptor, filmmaker, and artist, with butterflies, bees, and other pollinators appearing often in her work. Photos courtesy Alhondra Lopez.

Lopez says that monarchs keep moving between Mexico and the U.S. because they “found home in both countries.” But for Lopez, monarchs don’t make labels with countries, territories, or barriers—only humans do that. “Borders can separate us and make us feel different from each other. But I hope people understand that many of us who immigrate are not doing it because we want to, but because we are seeking warmth, seeking opportunities.”

After graduation, Lopez hopes to learn from different cultures around the world and then pursue a PhD. “I want to work for organizations and sanctuaries that protect wildlife. I want to become a leader in my community as a person who teaches and supports conservation.”

As a student of Environmental Studies, Lopez says she has recognized how environmental issues affect human communities—especially those who are marginalized. Early in her career as a student, she went on a trip around the western U.S., learning about culture, sustainability, history, and entangled issues from various communities. “Many people who spoke to us mentioned that global ecosystem changes are affecting them personally and creating complex situations. That’s why I have come to believe that enjoying the outdoors is more than having a good time with family, but also includes having a responsibility to our surroundings.”

Monarchs In Peril

Lopez says that the last time she went to see the monarchs, it was not the same. There were more cars, less greenery, and a different feel at the conservation site.

Most notably, there were fewer monarchs.

Monarchs are facing a global decline, plummeting 85% in just two decades, with the western population down 99%. The Center for Biological Diversity reports that “overall, the migrating populations are less than half the size they need to be to avoid extinction.” From pesticides to development, the threats facing monarchs are landscape-scale. Their situation is grave.

But many communities are fighting for these delicate-yet-resilient insects. Some are planting pollinator-friendly gardens or replacing lawns, while others are addressing overuse of pesticides or restoring the riparian areas these species need to thrive.

Monarchs cover the trees at a migration site in Mexico. These butterflies have seen crushing declines in the past twenty years, but they still gather together to stay warm. Photos by Sierra Hastings.

In the midst of this urgent work, scientists realize that basic information on the population trends and habitat use of monarchs—and many insect species—is sparse. Community science work like Utah Pollinator Pursuit gathers groups of concerned communities to help answer questions about the species before it’s too late. In this project, volunteers across Utah collect information about monarch butterflies, caterpillars, and eggs. They also record data about key pollinator habitat as well as bumble bees, whose populations are also facing alarming declines.

Conservation specialists can use this kind of large-scale data to support targeted conservation of these species and their habitats. In projects spanning landscapes and countries, the work of smaller groups unites to become something larger: hope for the monarch.

Diversity for Ecosystem—and Cultural—Resilience

With Lopez, the Sageland Collaborative team envisions a future full of pollinators and intercultural exchange, with bright migrations continuing well into the future. We hold that trees at migration sites should know the warmth of a thick coat of monarchs, and that human spaces should embrace diversity as a key part of a thriving, resilient community.

As we work to mitigate serious threats to monarchs, other wildlife, and lands, we feel strongly that these threats cross borders, ideologies, politics, and languages, wrapping all of us into an international, intercultural community of care. Social and environmental issues cannot be cleanly separated, and solutions require the weaving of many voices and knowledges.

“Nature is in us, and we are in nature,” says Lopez. “Nature is us.”

Young leaders like Lopez are inspiring conservation across the West. “Being part of the generation that is breaking the rules and raising their voice to change what is wrong has taught me the importance of sharing knowledge and speaking out.” Lopez says that past norms do not justify current behavior and conservation needs to happen now. “This planet is an art piece that should be respected and protected. We have everything in front of us.”

“My heart once told me to listen to the Earth sharing the smiles of all the spirits that are part of this planet,” she reflects. “I listened.”

Learn how you can support butterflies in Utah on the Utah Pollinator Pursuit page. And if you haven’t yet done so, please consider donating or volunteering to support the conservation of monarchs and other wildlife species into the future.

Written by Sarah Woodbury and Alhondra Lopez.

Artwork and photos of Lopez and landscape courtesy Alhondra Lopez. Monarch photos by Sierra Hastings.